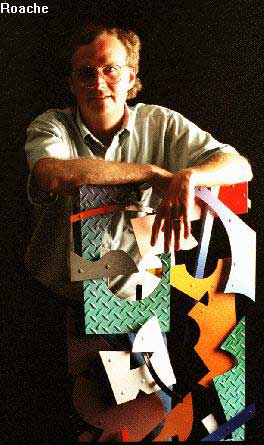

Artist: Daniel Roache

As Ferris begins its 20-year Renaissance movement, the first piece in the Presidential Art Collection, a creation by Daniel Roache of Petoskey, will be on permanent display in the Williams Auditorium lobby.

The Collection calls for a work of art to be dedicated each year to a Ferris president, past and future. The Roache work was dedicated to former president William A. Sederburg.

Sederburg was a long time supporter of the arts during his legislative career in Lansing. He chaired the General Government Committee that financed the arts in Michigan. He received a number of awards from the Michigan Arts Council for being an advocate of the arts. Since assuming the helm at Ferris, he was struck by a lack of the artistic element on campus. He decided to implement a long range goal to create a more artistically interesting campus.

Roache, a painter, printmaker and metal sculptor formerly of the Detroit Institute of Arts, sculpted an abstract representation of the seven academic colleges at Ferris from painted and cut aluminum. The sculpture is three-dimensional, approximately 30-by-40 inches around the perimeter and four inches deep, and will be bolted into a wall in the Williams Auditorium lobby. According to Roache, the piece is very "people proof."

Roache cuts shapes to represent people and things from the metal that he said "had former lives as stop signs and storm doors." He added in jest that he cuts around the bullet holes.

"Some people do sculptures from found objects," said Roache. "My philosophy is that found objects are meant to be lost.

"I prefer to analyze, and sometimes agonize, over the placement of every element of design," he said. "The fact that it is much easier to change one’s mind with an eraser than with a band saw, drill press and rivets makes me think over my composition and not depend on the ‘happy accidents’ that expressionist painters can count on."

His sculpture came out of his painting, Roache said. He noted that paintings are not meant to be touched, and that paintings are only two dimensional. By spreading out his work in terms of depth and texture he is able to create work that can be experienced by its viewers through touch.

The artist begins with a drawing in pencil. He then blows his drawing up to a cartoon. He makes patterns and cuts the metal shapes with a band saw. Taking the raw metal, he screws the pieces together to hang and check for structural problems. Assured that the piece will hang as planned, he disassembles the sculpture. He then plans the color, and paints each piece in lightfast enamels and automobile paints. After drying, he permanently reattaches the pieces to complete the work.

Roache is as concerned with the shape of voids between pieces as he is with the painted surfaces. He strives to make all parts of the design hold the viewers’ interest -- adding a bit of mystery, and making it complicated enough that it cannot be taken in with one brief glance.

"I feel that any work of art which is simple enough to reveal itself with a glance may be theoretically ‘valid’ as art, but to my mind merely decorative," he said. "In a short time art that is so minimal becomes as ignored and invisible as the furniture we live with. I strive to create an image that can be visited again and again, always revealing something new."

Roache studied drawing and painting in the studio of Michigan artist Ruth Loring-Janes from 1965-72. He was employed as a toolmaker and skilled machinist from 1974-75 while he studied art and art history in Detroit area colleges. He also studied at the Detroit Institute of Arts, where he was employed as special exhibition staff and as an assistant in the DIA Research Library from 1975-1980. He studied painting from 1980-86 with Michigan artist Karl Staber.

In addition to his work at DIA, Roache served as an instructor of painting at North Central Michigan College in Petoskey and in stained glass construction for the Henry Ford Museum education department in Dearborn. From 1987-90 he was co-owner of the Bridge Street Gallery in Charlevoix.

His work is held in the collections of Michigan National Bank Corporation; First of America Bank; Edsel Ford; Grand Rapids Community College; Loyola University in Chicago; Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan; Governor John Engler; Michigan Commission on Art in Public Places of Saginaw; Hutzel Hospital in Detroit; American Standox Inc. and Munson Medical Center in Traverse City.

In The Words Of The Artist. . .Remarks By Daniel Roache

I would first like to thank Ferris State University and president William Sederburg for your patronage to me personally and for support of Michigan artists in general. What you have initiated with this presidential collection is what art organizations such as the Detroit Institute of Arts and various arts councils couldn't see their way to doing.

Ferris did not waste money on a committee to "Increase the Awareness" of Michigan artists. You did not add a salaried position for someone to run a project for the "Advocacy"of Michigan art. NO, -- you bought ART! It's a great concept that I hope catches on. You now have a tangible that can be viewed, admired, hated or ignored for many years to come.

My former employer, the Detroit Institute of Arts, spent tens of thousands of dollars on their ironically titled "Ongoing Michigan Artist Program" which ended after about three or four years with very little to show for it. There was some Michigan art exhibited, but I dare them to prove it. They did not add to their permanent collection.

The investment Ferris is making in building a collection of art objects doesn't just serve to improve the looks of the school or the mood of the staff and students. As the collection builds in the long run, it will serve as a teaching tool for the creative arts department and for other disciplines as well. It's no accident that many of the oldest art schools in the country are attached to major art collections. I think, however, that it is a major mistake that both the instructors and students of the last thirty years or so have forgotten to look at those collections. Instead, they've often opted for the inbreeding of art instructors that have never had to deal with the art consuming public face to face.

I should probably get off of that subject except to say that you are very fortunate to have Robert Barnum here at Ferris. Robert's a valuable asset to Ferris. He's a productive and respected artist that can teach and, forgive me for using this phrase, but he has been out in the real world of artistic commerce outside the university setting. Although some may say that the art world doesn't qualify as the real world either, the world of commerce certainly does.

The objects and the ideas of an artist will last beyond his or her years if they're lucky. This a part and parcel of the artist's ego, I suppose. We all want to leave something behind. The idea I leave behind in my artwork which I have titled "Practical Academe" is, despite the title, open to any interpretation as all public art should be. In you alumni magazine it was noted that this work is a symbolic or abstract representation of the seven academic schools within the University. I think I put in enough figures to cover that number, but if you still don't see your department in here, please just imagine that the guy at the top wearing the red tie is thinking of your particular field.

By "Practical Academe" I simply mean to communicate that those educational experiences I most admire are those that have immediate utility for the student and are not so esoteric that they can be suspected to be part of a cult. You've all seen such course offerings and I needn't digress on that here.

Those artists who are so opaque and yet insistent on one interpretation of their work that they need to attach a three-page manifesto to their paintings deserve the sparse audience that they get for their work. In my own work, I attempt to reach a broad audience by splitting the difference between my fascination with the purely abstract compositional elements while still providing a bit of narrative content for those viewers that find the raw geometry of the underlying structure intimidating or boring.

Some of the subject matter as well as my design is implied by means of one of those arty catch phrases "negative space." Shapes and subject matter are defined not just by what is there but also by what is not there in those voids between pieces. Even colors that are not physically present in the work can be subconsciously "implied" by means of surrounding those voids with complimentary colors to create an after image with a phenomenon known as simultaneous contrast.

Materially, my wall sculptures as I call them, are made of aluminum for light weight and to avoid rust problems in outdoor settings. The pieces are riveted together and air brushed with automobile paints making them quite durable. Not all, but some of the materials, have had former lives as stop signs and storm doors. I do my best to make sure this fact is not evident in order to avoid having some curatorial type or art critic try to intellectualize the use of recycled traffic signs into having some deeper meaning at a later date when I can't defend myself or my art.

At this point I think I had best close this bit of fuzzy artist rhetoric before you start thinking that all those heads that are represented by negative space are in the art department.