Although Michigan was a citadel of Republicanism from 1854 until Franklin D. Roosevelt's election as president in 1932, W.N. Ferris was elected governor of Michigan on the Democratic ticket in 1912. He had been a Democratic candidate for governor in 1904 and a candidate for the U.S. Congress in 1892, but did not campaign for either post and lost both elections.

He was elected governor in November 1912 by a scant margin of 194,017 votes to 169,963 for his nearest opponent, Amos S. Musselman.

On Jan. 2, 1913, Mr. Ferris made his initial address to the state Legislature. Some of the things on which he hoped the Legislature would take action showed his major interests.

He asked for sanitary school houses, the divorcing of school boards from partisan politics, a uniform system of textbooks, and the preservation of the primary school fund. His plea for sanitary school houses is worth reporting because it showed the effect of his early schooling, and his problems with Old Main's plumbing. His description of conditions at the time are in decided contrast to those of today's public schools.

He asked for sanitary school houses and the divorcing of school boards from partisan politics.

"For more than a quarter of a century," he said, "I have made a careful study of school houses in Michigan. The majority of them are unsanitary and unfit for 'livestock' to occupy. They rarely furnish adequate light, never furnish a proper supply of pure air, are not comfortably heated, and on the whole are destructive to the health of school children. It should be remembered that the ordinary school room, unlike the ordinary dwelling room, is frequently occupied by a very large number of children. Probably no one reform would exert a greater influence in reducing the death rate of children than would the construction of sanitary school houses. Ordinarily school officers know very little about modern sanitation. It is largely a question of how large a 'pen' is required to protect the boys and girls from inclement weather."

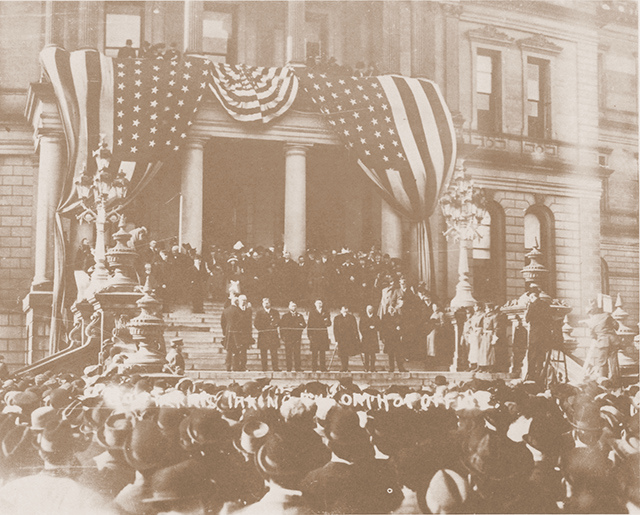

Woodbridge N. Ferris is inaugurated as governor of Michigan, January 1913.

Woodbridge N. Ferris is inaugurated as governor of Michigan, January 1913.A law should "be enacted whereby all plans for school houses should be submitted to the Superintendent of Public Instruction and Secretary of the State Board of Health. These officials would approve the heating, ventilating, lighting; in fact, all of the sanitary essentials before the contracts could be entered into for construction . . . ."

He made the same pleas in his speech before the Legislature on Jan. 7, 1915, after his election to a second term as governor. In those days the Legislature met only every other year, and the Governor served only a two-year term. There was no "state of the state" message in 1914.

Mr. Ferris apparently could never forget his Illinois school board experiences, and in his 1913 legislative message he also called for this reform:

This was the scene on Jan. 1 1913, as W.N. Ferris took the oath of office.

This was the scene on Jan. 1 1913, as W.N. Ferris took the oath of office."So far as possible, our educational interest should be divorced entirely from partisan politics. In Michigan, we have not succeeded in doing this. I suggest the enactment of a mandatory law providing for city boards of education of not to exceed seven members, elected by the people at large. Such school boards should be supervisory and legislative in their function and should have the appointing of two salaried executives, a superintendent and a business manager, each of whom should be responsible for his particular work." He repeated this plea in his 1915 message to the Legislature.

Mr. Ferris always claimed that it was his alumni who rallied to get him elected governor. Historians say that it was a split in the Republican party which gave him the slight margin of votes. Later, historians agree that it was Mr. Ferris' overwhelming popularity which got him elected to the U.S. Senate in 1922.

"A pamphlet advocating the candidates' stands should be mailed at the state's expense to every registered voter."

Mr. Ferris also claimed that he motivated the alumni to vote for him through the numerous speeches he made as publicity campaigns for his school. Knowing how careful Mr. Ferris was with his money, it is unlikely that he spent much on advertising.

In his 1913 address he asked for an election pamphlet published by the state. His plan was that each candidate for every party pay a nominal sum to have a certain amount of space giving his biography and view of public questions. The pamphlet would also include the text of all propositions and an argument for or against by its most active advocate or enemy. This pamphlet would be mailed at the state's expense to every registered voter 90 days before election.

Very few of the ideas Mr. Ferris presented at the time were considered feasible; the election pamphlet was one of them. It does seem, however, that it could be the preface to our present-day equal time mandate of the news media.

| Previous | Next |