By the time the 60's rolled around, Ferris Institute was no longer a fledgling state college. It again began to have budget problems. In the middle part of the decade, town and gown relationships were far from cordial, and by the end of the decade student unrest had nearly reached a fever pitch.

At the same time there was such a spurt in enrollment that many students had to be turned away or put on waiting lists. In fact, there were more students turned away than had been totally enrolled for many years.

The fall quarter enrollment for 1960 was nearly 3,350. Nearly 1,000 more were not accommodated. By the 1961-62 year, nearly 2,600 students were turned away while 3,673 were enrolled.

The 60's was also a decade of great physical expansion and academic program enhancement.

The 60's was also a decade of great physical expansions and academic program enhancement.

Throughout the 60's most homecoming weekends included the dedication of two residence halls. To provide for approximately 500 additional students each school year, the College had to be able to accommodate that many more students on campus. Residence hall construction continuously changed the campus skyline.

The last of the residence halls was dedicated in 1969. Named for William D. Cramer, a longtime botany teacher, it was twice the size of the other residence buildings -- 11 stories high, accommodating 600 students. Instead of four-person suites like the other residence halls, Cramer Hall had six-person suites.

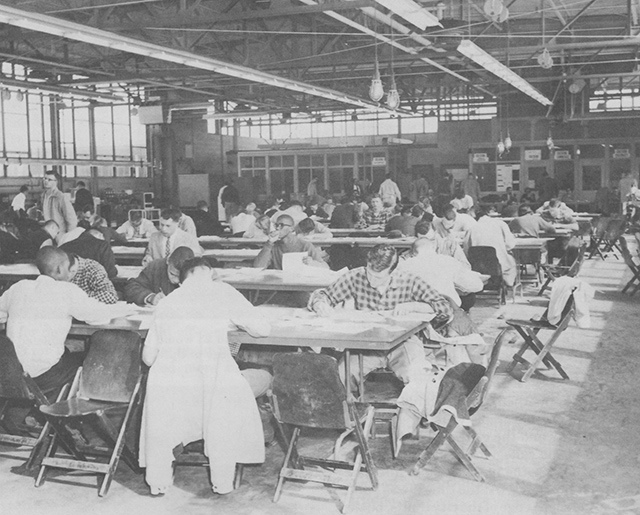

Before computers registration sometimes was a laborious process. As enrollment burgeoned,

the largest space available was utilized. This is the auto service floor.

Before computers registration sometimes was a laborious process. As enrollment burgeoned,

the largest space available was utilized. This is the auto service floor.Cramer Hall had its problems. Many students didn't like to live there. They didn't like the six-person suite idea, and they didn't really like 600 persons living under one roof. Something about it seemed to bring out the worst in the students. Eventually the room ratio was changed to four in a suite.

The whole West Campus complex was victim of a city-college clash. There were water pressure problems accentuated by the West Campus buildings. Someone decided that if all the students living on the West Campus got together and flushed their toilets at the same time, there wouldn't be any water in the rest of the community for several hours.

The result was a conflict between the city and the state government. The city thought that the college (via the state) should pay for the additional water facilities. The state said, "No." In fact, the state said in effect, "If the problem can't be resolved, just close down that section of the college."

The Chamber of Commerce came to the rescue and a bond issue was floated which provided for the construction of two water towers to be paid for by water users.

Looking back it doesn't seem like much of a battle, but at the time it was a full-scale war.

This is the architect's drawing of the way dormitories 21, 22, and 23 would look when completed. Pennock Hall on the right has been redesigned to serve the College of Optometry.

Construction was a common sight on campus in the 60's as dormitories want up one after another. Here, building is in progress on the Puterbaugh-Henderson complex on West Campus.

In the long run, then, the city built four water towers to provide ample water pressure for the community and the college. The first one, just north of the college on State Street, was built shortly after the fire of 1950 to alleviate any further problems. (At the time it was built, it was at the south edge of the city limits, but as the college expanded south, the city limit signs went with it.) The second water tower was built at the south edge of the campus when the South Campus units were being built. After the West Campus addition, one water tower was built to the western edge of this addition, and another was built across the Muskegon River in the eastern section of Big Rapids, now the city's Industrial Park.

Several years before West Campus was planned, the city and college were embroiled in another "war" where some uncomplimentary words were bandied about between President Spathelf and the mayor of Big Rapids, Don Page.

This controversy was not without precedent.

In 1959, John, Robert, and Barbara Bergelin had bought a 40-acre farm west of the city, intending to hold it for the site of a new high school when the time came to build a new school. Members of the school board and some of the city residents fought the site on the premise that the Bergelins were going to make a profit on the land. The Bergelins, however, maintained they were only trying to do the school board a favor by buying the land when it was available, and then selling it for the amount they paid when the city wanted it.

On the supposition that this spot which would have been relatively inexpensive was too remote, especially for the residents on the far eastern side of town, a new site for the high school was found in the city's Hemlock Park area on the river.

The Bergelins held on to the property. Through some purchases assisted by friends of the college, Ferris had bought some acreage on the west side of U.S. 131 and began to make plans for expanding the campus that way.

In the 60's, when college and university enrollments were booming, it became a popular idea for developers to build off-campus apartments for university students. In many cases the developments provided more headaches than they did profit.

This is the same argument Mr. Ferris used in 1891 when he thought the community was discriminating against him.

In 1966 a developer bought up most of the Bergelin-owned farm, asking the Big Rapids Plan Board for a rezoning. The Plan Board complied, as did the City Commission, over Spathelf's objections. In this battle there was some name calling, some sides taken, and some friendships sundered.

Spathelf said that the apartments planned would impede the progress of the college's development to the west and that it might mean the school would have to move to another city.

This is the same argument Mr. Ferris used in 1891 when he thought the community was discriminating against him.

But the Hillcrest Apartments were built. Heated discussions continued, but eventually the property owners and the students got their pieces spoken and things quieted down. There was nowhere else to go, and the college continued its expansion plans for West Campus.

The 11-story height of Cramer Hall presented another problem. City ordinance limited buildings to five stories, but since the college was on state property the ordinance didn't apply. There was much concern over the city's limited fire fighting equipment. Neither the city nor the college had any money to buy new equipment. Eventually this problem was worked out to mutual agreement, but it was not until 1980 that the city got a ladder truck tall enough for the hall.

| Previous | Next |