Ferris State Alumni Association

420 Oak Street, Big Rapids

(231) 591-2345

In the ninth inning of a Cleveland Indians game at Jacobs Field, the visiting Toronto Blue Jays, down by a run, have men on first and second. The crowd is booing any close pitch the umpire calls a ball.

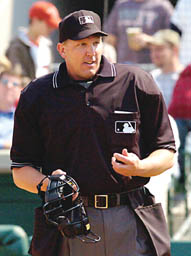

For the vast majority of baseball fans, the umpire is at once a darkly mythic figure who potentially holds their team's fate in his hands, yet someone who is almost anonymous, who unlike most players does not have his name spelled out across the back of his uniform.

Behind the plate this unseasonably cool August evening, Jeff Kellogg (EHS'83) holds up his hand to stop the action or points to the pitcher to get things going again with an umpire's requisite confidence. For Kellogg, such confidence is part of what it takes to make it in the big leagues.

"When you're on the field, you can't show indecision -- because the minute you do, they'll eat you alive, whether it's managers or players. You just have to be cool."

Kellogg is displaying that cool he has exhibited in 12 seasons in the big show - a cool he first began perfecting as a Criminal Justice major at Ferris State University.

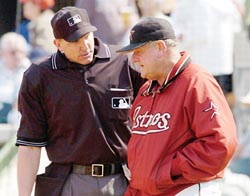

When explaining a call to a manager, whether John Gibbons of the Toronto Blue Jays or Jimy Williams, formerly of the Houston Astros, Kellogg can call on his Ferris Criminal Justice training.

It was at Ferris in 1980 when Kellogg found himself following a televised game that would lead him to his ultimate career.

"I was watching a Saturday game of the week," Kellogg remembers. "A guy from my hometown of Coldwater was working that game. When he went out to break up a conference on the mound he had his mask off, and I said, 'Oh my gosh, that's Tim Welke!' I knew he was an official, but I didn't know he'd made it to the big leagues. When I saw him, I said, 'You know, I think I could do that.''

He talked it over with his parents and decided to finish his education before pursuing a career in sports.

Following graduation, Kellogg spent a year working at the Branch County Sheriff's Department. After almost exactly a year on the beat, he traded in his badge for an umpire's mask and never looked back.

After umpire school and a minor league development program, he began calling games for the Class-A Appalachian League, which started his rise toward the major leagues.

"In 1986-87, I was in the Midwest League, which is A-league, then in 1988-89 I was in the Eastern League, which is double A," Kellogg says. "During 1990-92 I was in Triple-A. In 1991 I also worked five games in the big leagues, and in 1992 I worked roughly 50 big league games. In 1993 I was hired full time."

Since then, Kellogg has worked two World Series, in 2000 and 2003, as well an All-Star game. He cites the 2000 "Subway Series" between the Yankees and Mets as the highlight of his career.

Having to concentrate on calling the World Series at Yankee Stadium required Kellogg to forgo some of the jitters he might otherwise have had in what is arguably the most hallowed diamond in the history of the game.

"I've heard umpires talk about when they walked on the field at Yankee Stadium for the first time and how they were thinking about the great players who have played there," says Kellogg. "I couldn't do that because I had to focus on the game. The first time I worked at Yankee Stadium was that World Series, because I was a National League umpire for the first eight years of my career before the staffs were combined.

"When you start umpiring, you want to get to the next level, then the next level after that. Once you get to the big leagues you want to work the World Series. It's the ultimate goal for every umpire. Then to have that series be the Mets and the Yankees was pretty neat."

Despite the growing popularity of football, soccer and auto racing, and in spite of 24-hour-a-day sports global cable programming that can bring everything from beach volleyball to sumo wrestling into viewers' homes, baseball maintains a special place in the American psyche. Kellogg, like many Americans, played organized baseball through Little League to American Legion games to high school competition. Growing up, he also had his favorite team - the Detroit Tigers. So it's not so surprising that when Kellogg thinks back to the time he was most in awe of being on the same field with national sports heroes, it wasn't his first major league game or even the World Series that he remembers, but a pre-season game.

Kellogg has climbed the umpiring ranks from single-A minor league games to calling the World Series.

"As a kid I just loved the Tigers: Trammell, Whitaker, Gibson, all those guys," Kellogg says. "So the biggest time when I thought, 'Wow, I'm on the field with these guys,' was spring training when I worked a Tigers game and some of those guys were still playing."

The biggest challenge that Kellogg faces as an umpire doesn't come on the field. Traveling almost constantly for six months keeps him away from his wife Roxine, daughter Sydney, and sons Trent and Holden.

"I'm packing and unpacking every three days for half the year," says Kellogg, "but there's also a lot of good that goes with it, too. My family gets to travel and see a lot of the country. My kids have been to two World Series. So there's some positives, but the biggest negative is being away from them so much."

Family matters also figure into one of Kellogg's most distinct officiating memories. With so many calls made in any given game, few individual plays remain memorable over the years -- although one that does came early in his career.

"A play that stands out for me was one in A-League ball," Kellogg says. "It was one of the first times my mom and dad came to see me work. My little sister who was 6 or 7 at the time was there, too. I had to eject the manager for the Kenosha Twins, who proceeded to throw a bucket of balls and some bats at me. After the game my little sister came up to me crying, wanting to now why he was doing that stuff. I had to explain that he disagreed with one of the calls I made. That really brought home the fact that it's all about family and the people who care for you."

Almost three hours after the first pitch, Cleveland Indian fans pour out of Jacobs Field to celebrate their team's 3-2 victory, their seventh in eight games, which keeps the team in the pennant race three games behind the American League central division leading Minnesota Twins.

Tomorrow night, Kellogg will rotate to officiate at third base for the final game of the series. After that, he'll be in Toronto, St. Louis and Chicago, then he'll head home to Mattawan, Mich., for a week's break. By contract he can't work two World Series in a row, so he'll continue to work up until then with his three other crew members, who he refers to as his "family away from family."

"It's a long season, it's tough to get up for every game, but you have to do the best job possible every night," says Kellogg. "I've had friends tell me that what we do looks easy. And I say, 'You know what, maybe we're there because we make it look easy.'"

But it isn't easy. Kellogg's job requires split-second decision-making, conflict-resolution and a commitment to seeing that the rules are equally and equitably applied and followed.

Asked if those qualities, along with keeping his cool, go back to his Ferris degree, Kellogg just laughs.

"Every once in a while I have to handle a situation similarly to how I would have to if I were still in police work, although it might not be a life and death situation."

Just don't try telling that to the manager of the Kenosha Twins.