Ferris State Alumni Association

420 Oak Street, Big Rapids

(231) 591-2345

First Lieutenant Shirley Razmus’ (EHS’01) children grew up seeing her in uniform and

thought that was the norm.

First Lieutenant Shirley Razmus’ (EHS’01) children grew up seeing her in uniform and

thought that was the norm.

“One day my daughter, who was about seven at the time, looked out the car window, saw a trooper helping a motorist and said, ‘Mom, Mom! That’s a police man!’” Razmus says, laughing.

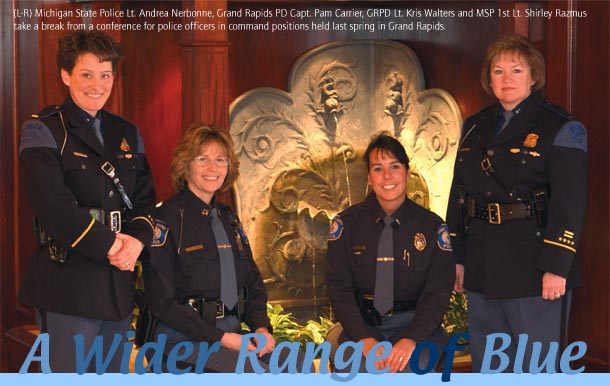

That was in the early 1980s, and while men generally haven’t been out-staffed in police departments, woman in uniform are increasingly common—as are women in command positions. Today, Razmus holds the top position in the Michigan State Police’s Rockford post where she oversees five sergeants, 30 troopers, eight dispatchers, a detective sergeant, six radio techs and two motor carrier officers.

While Razmus doesn’t think of herself as a role model, others do. Just ask her second-in-command.

The Rockford post of the Michigan State Police is headquartered in a two-story building constructed during the Great Depression by the Work Progress Administration. Its brick façade calls to mind the no-nonsense and almost all-male workforce of the WPA.

But in Shirley Razmus’ second-floor office, Lieutenant Andrea Nerbonne (EHS’85, ’01) explains some of the ways her boss has helped change traditionally male-dominated institutions.

“Because of people like Shirley, women like me can come into the field and not be hassled the way we might previously have been,” says Nerbonne. “I’m sure there are still some men who have sexist views, but my experience was of men and women in class together and in the academy together.”

“When I started in the ’70s, there weren’t many women in law enforcement, so there was some apprehension,” admits Razmus. “Once when I was a cub trooper, I was assigned to a new partner. Unbeknownst to me, he went to the partner I’d worked with the previous shift and begged him to switch duty. That trooper, who was male as well, said, ‘Just go work with her one night, and if you still want to switch, I will.’ I ended up working that shift and many other shifts with the new partner, so obviously I passed the test.”

Today, about 12 percent of the Michigan State Police are women, and the veteran Razmus spends little time worrying about gender issues. Most of her time is spent dealing with the day-to-day operation of her post—especially what needs to be done to implement the MSP’s new state-wide communications system—an essential task since the Rockford post handles about 60 percent of calls for the state’s second largest metropolitan area.

Grand Rapids Police Department Captain Pam Carrier’s (EHS’78) experience largely mirrors that of Razmus. Carrier’s office in the Grand Rapid Police Department’s recently renovated headquarters in the former Herpolsheimers department store could just as easily be any male captain’s office with its FDNY hat, NYPD coffee mug and certificates of various achievements—except maybe for the hand-made birthday card, which proclaims “We you, Mom” from amid an explosion of stars.

Although Carrier acknowledges that policing is still a male-dominated field in terms of total numbers, she says that’s not the whole story.

“There are more women in policing than ever before, especially in command positions,” Carrier says. “We still have some citizens that call and will want to talk to the male in charge and I tell them, ‘I’m the male in charge.’ Then they want to talk to my lieutenant. Well, my lieutenant’s female. So there’s still a small part of society—and I’m sure a few male officers—who feel that we shouldn’t be here, but I think that by and large people accept us.”

Lieutenant Kris Walters (EHS’84, ’01) agrees. “I was introducing a high-school intern I’m working with—a female who’s looking at a career in law enforcement—to the people in the department and she said, ‘Wow, there’s a lot of female officers here.’ So I think our numbers are definitely growing.”

Both Carrier and Walters cite a number of changes that have contributed to the acceptance of women on the force.

“In Grand Rapids we went from being a department driven by 9-1-1 calls to a community policing philosophy of working with our citizens,” Carrier says. "Today you have to be more professional, more educated."

Walters thinks that women are well suited to this new policing reality.

“Officers find themselves dealing with situations with more finesse than physical skills,” she says. “It’s not accepted anymore to just go out and beat somebody up. You have to have more than just physical skills to deal with situations.”

According to David Holmstrom, writing for the Christian Science Monitor, the interpersonal skills women bring to the force may be exactly the direction law enforcement is headed—even if women are still a minority in most police departments.

“If day-to-day policing is less about force than about listening to both sides in domestic and neighborhood disputes, then some experts insist that women may be the top cops of the future,” Holmstrom writes.

That next generation of police officer is already on the street. And if Kerri Cannata is any indication, that kind of relationship-building is exactly what departments are already practicing.

Cannata is an Ottawa County police officer, one of three who patrols Allendale Township. “Regular road patrols might not form the relationships we do,” says Cannata. “We deal with issues regular officers wouldn’t. We talk to managers of businesses and people like that, so that when they have a problem that isn’t an emergency they can call and leave a message, and we’ll come out and deal with whatever the issue is.”

Like Carrier, Cannata says that any cultural shift that still needs to take place lies more with civilians than with her brothers and sisters in blue.

“I’ve been accepted very well by my co-workers,” she says. “I haven’t felt I’ve faced any discrimination. In the field, I think that some citizens still view us differently. Sometimes people are surprised that a female shows up at their door. A lot of times when I get out of the car I’ll hear little kids say, ‘She’s a girl!’’’

Cannata was the outstanding recruit from the Michigan Police Corps 2001 Police Training Academy graduating class. She also was class commander. Recruits vote for class commander based upon character, physical ability and academic success throughout the academy.

So while there aren’t yet a lot of people, like Razmus’s daughter, who cry out in wonder at seeing a policeman, it seems likely that people like Cannata, recognized by her own peers as a leader, will continue to bring a new range of leadership skills to a career-path that each year has more, and more-complex, challenges.